|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

「義孝と源保光の娘/高内侍と道隆」 (Yoshitaka to Minamoto Yasumitsu no Musume/Kou Naishi to Michitaka)

“Yoshitaka and the Daughter of Minamoto Yasumitsu/Kou Naishi and Michitaka”

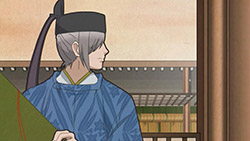

Uta Koi’s second arc brings two new stories to center stage, both linked by the same sense of loose continuity that punctuated the vignettes in the previous arc. It would appear Yoshitaka (Ishida Akira) is this era’s Narihira, only the suave, gravitational charm is replaced by an almost flowery and Zen demeanor. This story may feel as if several pieces of the puzzle are still missing, and this is most likely due to how anachronistic Yoshitaka’s courting of his fiancee is. With the advent of face chatting, mobile phones, and even things like airplanes and cars, being “connected” to another person has become so easy… to a point it’s easy to take the luxuries afforded by those methods for granted. Expressing feelings and moving through the stages of love have all been facilitated somewhat by technological revolution, and even the regression of the strict traditions imposed by ancient society have led relationships to blossom a lot more easily and being unable to convey one’s thoughts and feelings seem nigh impossible because of the numerous possible ways of doing so.

The above clearly is not the case in the time period of Uta Koi, and it contributes to how out-of-date and seemingly loveless Yoshitaka’s relationship is. Communicating solely through letters is a rather limiting and almost stagnant way to advance a romantic relationship, especially if two people involved in it are to be wedded. Of course, a large part of this is due to the social traditions of the time, but it’s difficult to really grasp the fact Yoshitaka loves his soon-to-be wife when he has only interacted with her through letters. In this era, letters, aside from speaking with the other person, is the furthest the romantic frontier has expanded, which seems incredibly slow and ancient considering how developed the dating stratosphere is today. It’s as easy as pressing a button to share any moment of a person’s life and that has become the expected norm; anything else is dubious, and it’s difficult to fathom how one could convey emotions through anything less than a dozen Facebook status updates, tweets, and emoticon spams on SMS. The simplicity of things in Uta Koi, while not easy to fully understand, is a much appreciated break from the hectic overload of modern day courting.

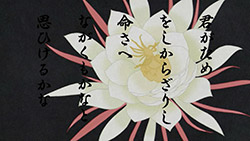

Hyakunin Isshu #50 by Fujiwara no Yoshitaka

This translation, assuming the portrayal of Yoshitaka in Uta Koi has some reality embedded into it, is probably the best snapshot of his personality. The tone of the poem is rather muted, but doesn’t feel as distant, as words such as “precious” and “eager” help to inject some color into the verse while keeping it in form. “Desire” is probably the one word that really helps to illustrate the importance of his love – it is the one descriptor of passion, and no other word – save for “precious”, perhaps – has the impact as “desire” does . It brings forth a somewhat wild, unbridled emotion when read aloud, which doesn’t occur with any of the other words in the poem; the significance here is that the rest of poem is eloquent, yet subdued in terms of pure emotional value and the grandness of his feelings. There’s an element of calm sweet devotion, but there is not the same sense of passion and gusto that stirs a desire to live from the depths of his heart. The fourth line is crucial in delivering that point across, and the following line helps to attach a lasting quality to his love. The long vowel sounds also lend a tone of sincerity to his sentiments, which helps temper the unrestricted nature of the word “desire”.

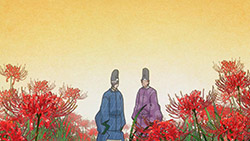

When all is said and done though, the second story revolving around Fujiwara no Michitaka (Kusunoki Taiten) and Takako (Hirata Eriko) feels fresher with the different perspective it brings, outlining the concerns of women at that time period regarding marriage. Not only that, this point of view comes from someone of the lower class, differentiating it from Yoshiko’s desire for freedom. Takako represents an interesting dichotomy to the women featured in Uta Koi so far, who have all been of high rank (Emperor/ex-Emperor’s brides). This is further emphasized by her tone of voice and appearance, which separates her from the depiction of noble women in this era. Her voice is a drastic difference to the high-pitched voices of higher-ranking ladies, and even the style of her hair differs from women with status. All in all, it’s a fairly detailed effort that was put into signify Takako’s social standing.

This is the kind of thing Uta Koi excels at, whether it means to or not. The poems are at the center of the show, but there are some subtle social commentary weaved in the interaction between characters that are simply wonderful to watch.

Hyakunin Isshu #54 by the Mother of Gido Sanshi (Takako)

The tone of the poem is, simply put, dramatic. This can skew the poem two ways: it may seem the speaker is exaggerating the situation, or it can also be that her pain is so difficult to endure that it warrants such extremes. It’s difficult to construe the true intention based solely on the poem, as it doesn’t offer enough context to present evidence supporting either argument. What is clear, however, is that the use of hyperbole is the key feature here. It is the main vehicle in carrying the speaker’s emotions across, and the absoluteness of her words does well in translating her frustrations into something palpable. This verse really needs proper context to fully understand the complexities behind it though, and this is definitely a case where a poem is benefitting from this adaptation. Of course, Uta Koi is simply just an interpretation and hence doesn’t carry any absolute truth, but whichever way the tale is spun, this particular poem is much more enjoyable with something built around it to offset the jarring hyperbole.

Full-length images: 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 15, 18, 19, 20, 24, 25, 26, 29, 30, 31.

Preview

|

i miss Narihira already. ~_~.“

still need time to get used to Yoshitaka as the pivot character in this mid-Heian era.

expecting Michitaka to continue to provide the comic relief, much like how Yasuhide did previously.

Joy – laugh – joy – cute – cute – joy – eternal sadness – joy – laugh – laugh – regret – joy – sadness – laugh

WHAT THE HELL I AM SUPPOSED TO FEEL AFTER AN (awesome) EPISODE LIKE THAT ?

I love Yoshitaka’s character. I’ve always been a sucker for gentle characters. Show Spoiler ▼

ah I’m sorry I forgot to put the SPOILER tag!!! In hopes that someone sees this… WARNING SPOILER ABOVE

Haha, no worries, I’ve fixed it, thanks for noticing though!

Spanish wiki says Show Spoiler ▼

LOLs, old man Fujiwara is HILARIOUS. I was already suspecting something with that ghost story he told Yoshitaka and Michitaka, but to take it to the next level like that was too much. Poor Michitaka almost had a heart attack! XD

Michitaka really did what he said isn’t he? That is according to Wiki…..