「康秀と業平 文屋康秀」 (Yasuhide to Narihira Fun’ya no Yasuhide)

“Yasuhide and Narihira – Fun’ya no Yasuhide”

I guess bromance is still romance… kind of. The interactions between the three poets Narihira, Yoshiko, and Yasuhide (Chiba Susumu) are at the core of this week’s episode, making it more of a character study rather than an episode dedicated to unfolding a love story. It’s certainly a welcome change since as wonderful as those stories are, they don’t offer much depth to the characters themselves, or offer a very skewed view of them – a perfect example of the latter being the last episode. I realize upon another look at it that the portrayal of Yoshiko is told mostly from Munesada‘s point of view, and is going to be heavily laced with his biases as a result. She’s presented through his eyes, so what Munesada interprets as Yoshiko’s thoughts are translated onto the screen, even during non-monologue scenes where she is speaking herself. Suffice to say, my criticisms of her character should have taken into account the skewed perspective that resulted from the episode being grounded on Munesada’s story to seem more objective and structured.

The fourth episode of Uta Koi presents the same sort of loose continuity the previous three episodes offered, and I like the idea of these poets co-existing at the same time – it gives a cohesive sense to the show’s universe, and the thought that they could have influenced one another (whether they did or not, I really wouldn’t know) lends a different perspective to the poems presented so far. Timeline-wise I’m not entirely sure where this week falls into, except to say it’s clearly before Narihira passed away.

Narihira is always a welcome sight, and I dare say this man is a charmer of epic proportions. He’s historically lauded as the epitome of the “beau homme”, and he definitely embodies every bit of that distinction. This episode takes a closer look at his character, and ties the idea of freedom within poetry back to the idea of using poems as a medium for one’s true feelings. I’ve touched on how melancholy that idea is before, and it’s enforced here as Yoshiko, Narihira, and Yasuhide all face restrictions of some sort they hope to escape from through words. Societal shackles once again play a huge role here, as Yasuhide stands on the opposite spectrum when it comes to wealth – it’s a painful way to judge people, but it is also the easiest method of determining a person’s worth. For people of no fortune, it leaves very little choice, even if they are brimming with talent. The confines of society become a difficult, if not impossible, hurdle to overcome. Poetry then becomes the symbol of freedom from those restrictions, as there is no individual value placed on words, only connotations. A poem’s worth is denoted (should be denoted, at any rate) by its atmosphere, the emotions and messages behind it rather than who wrote it. This is why an anonymous poem can flourish through the ages even though the author’s identity is unknown – what matters are the words rather than the person writing them.

For Yasuhide, poetry is his own, a brush he can wield to his liking and a clear symbol of his abilities. His conversation with Narihira is telling – it is an acceptance of who he is, who Narihira is, and what makes them different. It is a moment where Yasuhide recognizes neither his social standing nor Narhira’s social standing has as much influence on who they are as poets as he assumed. “Freedom” is a subjective concept, and it probably means different things to the two men. The conversation is a wonderful depiction of Yasuhide coming to terms with who he is. His background, although poor, is his own and it affords him experiences and emotions that are completely his own, that no one can imitate. The recognition of his self-worth was great, and watching Yasuhide finally stand on equal ground with Narihira as poets was a fitting end to the episode. It was he himself holding him back from acknowledgment, not social standing, or Narihira’s sheer greatness.

The rest of the post is spoiler tagged for convenience.

Show Spoiler ▼

Narihira is, I find, somewhat of an enigma. His character is always presented through someone else’s eyes, and there are several different facets/interpretations of who he is as a result. He certainly makes an impression on those he interacts with, and while the premiere presented Narihira the Lover as well as Narihira the Brother; the second episode depicted Narihira the Mentor; this episode strives to capture Narihira the Poet. I don’t think there’s a complete portrayal of Narihira the Person just yet, but a clearer picture is definitely starting to be formed by linking all three together. I don’t think it’s coincidental he’s never presented directly, and the distance can be interpreted as a “restriction” he must face. The “closest” the audience has ever gotten to experiencing Narhira’s character firsthand is in episode one, and it’s apt since the distance between lovers is closer than most other relationships. It’s strange then, that the familial relationship between Yukihira and Narihira seems so distant. Taking into account the criticism of Narihira’s poem at the beginning of this episode and how he is portrayed as a poet into consideration however, one can make the assumption Narihira’s real character is closest to that of a lover. Passionate by nature, with all precedence given to expressing emotions rather than organizing them.

There’s a noticeable distance between the audience and Narihira in this episode, which is in part due to the fact the episode is presented from Yasuhide’s point of view. In Yasuhide’s mind, there is an immeasurable distance between him and the renaissance man, and that carries over to how the audience’s interpretation of Narihira’s character. He feels far away, and I feel this episode is the furthest distance Uta Koi has ever put between him and the viewers, strongly suggesting defining Narihira in societal terms is the wrong thing to do. It is a cage – not only for the narrator, Yasuhide, but for Narihira as well.

There is an innate desire in every person to be recognized by their abilities alone, untempered by titles and gender and wealth. Rich or not, no one wants to be judged by things they cannot control, and there’s a clear sense Narihira shares the same sentiments as Yasuhide – it’s just that the latter does not realize this until the end. Poetry is every bit a representation of freedom for Narihira, reinforced by the fact the use of poems as a means to express oneself was first heard from him. It had a profound effect in the episode it was presented in, but it continues to make ripples even now as the audience sees just how invaluable and precious poetry is to poets. Each person finds themselves restricted in some form or other, and being born of status can be just as detrimental as being born poor. For the rich, conduct becomes meticulously dictated, and upholding reputation is the name of the game. “Truth” becomes a relative concept in the upper echelons, a fact that can become oppressive and difficult to bear. For Narihira poetry affords a sanctuary from politics and societal expectations, which is also probably why his works are criticized as “passionate” and “lacking eloquence”. They are a reflection of a life he can never have, and the unbridled emotions now carry a bigger meaning than it did back in the first episode. They’re not just expressing the grandness of his love, they’re expressing him, period.

I’ll hold off on Yoshiko’s analysis until next week to keep the post as short as possible, but also because I feel it would be more relevant when her poem is actually presented.

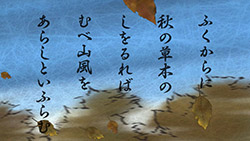

This week’s poem is arguably the most difficult to hack apart since it involved a play on words in Japanese that’s difficult to reproduce in the English language. It’s even harder to try and analyze this, but after bit of thinking, this is what I came up with:

Show Spoiler ▼

It is by its breath

That autumn’s leaves of trees and grass

Are wasted and driven.

So they call this mountain wind

The wild one, the destroyer (Ogura Hyakunin Isshu)

These observations are probably a stretch, but considering Yasuhide’s struggles and what poetry means for him, the mountain wind could possibly represent social standing.The “wild one” gives the impression there is no order, which can seem contradictory to the strict organization of social hierarchy. But wild can also denote a lack of sense, and that interpretation makes sense from the point of a beleaguered man trying to make ends meet. To him, there is no logic behind being kept from doing what he wishes to do because of a lack of wealth. The image of “destroyer” further enforces this thought, painting the emphasis on wealth as something sentient capable of destroying the autumn’s leaves that dare to dream. The poem gives the implication that without this force, the fragile leaves and grass would be allowed to thrive, a legitimate question that can be asked of the structure of society.

Autumn’s leaves and grass represent the poor, and it’s apt since leaves are widely considered to be weakly attached and powerless, blowing everywhere at the slightest provocation. They lack a foundation to stay rooted, and the metaphor works since the fate of the poor is often driven by the rich. Grass also works as it is easily stepped on, often ignored and not considered as people walk all over them. The poem gives the sense the fixation on wealth and status quells the beauty of nature, extinguishing hopes and dreams of the less fortunate even before they have a chance to sprout and grow.

Like I said, while this analysis does work, I don’t know how valid it is and I’m not a huge fan of this interpretation of the original poem. The imagery is far too strong for my liking, especially considering Yasuhide’s personality. I almost prefer CrunchyRoll’s take on the poem for once, since the same message can be applied there, but the presentation of it is done in a far milder style more suited to Yasuhide. With this translation, there’s a lot more negativity than there needs to be, and the episode shows Yasuhide to be melancholy and even meekly accepting of his plight, not downright angry and aggravated as the diction suggests.

Full-length images: 3, 8, 10, 12, 14, 15, 19, 24, 29, 30, 34, 36.

Preview

Thanks Bakamochi for deconstructing the poem. Please continue your good work, /cheer. 🙂

Thanks! 🙂 I think I was bit off the mark this week, though XP

I don’t really see this as a “bromance” episode – there’s no deep affection between Yasuhide and Narihara – as much as it’s about the love of poetry itself. And I took the poem as presented in the episode as an example of “art for art’s sake”, if you will – a poem that isn’t deeply symbolic or full of meaning, but an example of skillful craft and construction.

Yeah I wasn’t particularly gung-ho about my own analysis, to be honest – it works, but I have a feeling it wasn’t intended to be viewed like that. The translations were all godawful, too – well perhaps godawful is being too dramatic. All 3 “sources” I looked at had varying translations, so I figured there really wasn’t anything “central” the poem was trying to get across.

I guess I’m of the mind POETRY MUST CONVEY SOME DEEP MEANING, hence my tl;dr analysis.

Honestly, I have no idea if there’s a deeper meaning behind the poem – but I don’t think there is in the way it was presented by Utakoi. All anyone is really doing – including the mangaka here and Kana-chan in Chihayafuru – is guessing as to what the poems might mean. For me, Utakoi’s Yasuhide represents the craftsman vs. the artist – someone for whom poetry is most primarily a way to make a living, and not necessarily to plumb the deep dark mysteries of the soul.

For me the episode wasn’t really about the dichotomy between the craftsman and the artist or art for art’s sake. This has a Wildean concept of what the purpose of art actually is which I think the ideology of the episode directly opposes. We see art here as a conduit of self-expression and salvation for the two characters. It lets them act outside of societal norms. Yasuhide is bound by his class while Narihira is constrained by the accepted acts of courtship. Poetry paves a way for them to ‘rebel’ against the status-quo. The main reason for my belief is that neither Yasuhide or Narihira composed poetry to make a living. During the middle Heien period poetry was mostly considered an intellectual sport for the noble class. Considering that Uta Koi is billed as a ‘super-liberal’ interpretation of that time, I think the series as a whole is trying to shed light to the fact it was more than that to the poets in question. This all stems from the dual uses of the tanka, one as a description of nature, the other as a window into domestic issues. During the middle Heien period we see the use of the latter fall out of favor as it created political issues for many nobles. For poetry buffs like myself the show takes the stance: What if these were just not descriptions of nature? What if these were something more. If you dig a little deeper into the history it sheds a lot of light as to the meaning of the episode.

LOLs, that beginning skit with Teika and Tsurayuki dissing the poets and getting punished by Kuronushi was fantastic!!

*menacing tone of voice* “It’s not nice to shun people…” XD

I want those face painted fruits ._.

oh Narihira, thank goodness they haven’t taken you totally off the show after your passing away.

I love the faces on the mandarin oranges (are those mandarin oranges? or what?) so much! XD (Sorry for the randomness!)

Yeah, this certainly isn’t my favorite episode. I come for the romance, which kept me guessing as to whether Yoshiko and Yasuhide were going to fall for each other, as implausible as that seemed.

But it was still entertaining, and I found the discussion on how the purpose of poetry differs for people quite interesting.

And seeing Narihira again was great. Good to know the show isn’t done with him just yet.

lol Munesada wasn’t able to keep Narihira away

For the timeline, we’re in the (late) 840s, before 850 when Munesada took orders and became Henjo. It looks to me to be almost exactly a year after episode 3, but it could be two or even more (both episodes take place in autumn).