|

|

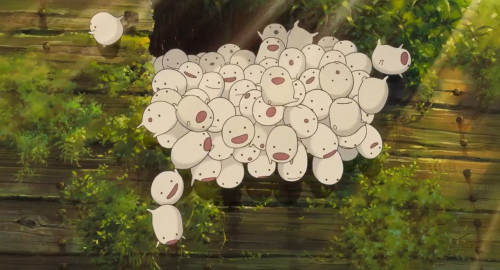

Unreasonably cute little boogers? Must be Miyazaki! |

I watched The Boy and the Heron with some mates the other day. I went in knowing nothing about what to expect and went out perhaps knowing little more. The film is a lot, full of imagery and symbolism interwoven within the tropes of a through-the-looking-glass fairy tale, where things are free to happen without, or even in defiance of, explanation. I would say it’s the most difficult to process of Miyazaki Hayao’s ouvre but since he went out of his way to come out of retirement yet again to give us another masterpiece the least I can do is unghost temporarily to write up my meagre commentary, specifically on why I think Miyazaki truly intends The Boy and the Heron to be his swansong.

(Bird pun intended but I couldn’t think of a better one).

I should warn that this post will only have scant summary and will flow freely with spoilers, being more of a debrief with those who have watched it. For those who don’t care about any of that, though, follow along as you please.

As a spiritual successor to The Wind Rises and another of Miyazaki’s arguably autobiographical films (more on this later), The Boy and the Heron is of course set in World War II, the event that no just reshaped Japan forever but also formed Miyazaki’s earliest childhood memories. The boy in question is Mahito, the headstrong son of a wealthy factory owner. In the opening act of the film, Mahito ‘s mother literally dies in a fire, traumatising the young child. With the danger and horror of the war so evident, Mahito’s father subsequently relocates himself and Mahito away from Tokyo to a countryside estate where Mahito meets Natsuko, his mother’s younger sister to whom his father had remarried. Against this backdrop enters the titular heron, which is no mere waterfowl. It lures Mahito to a tower on the outskirts of the estate; the old maids whisper that it was built by Mahito’s great granduncle at an immense cost in blood and treasure, right before he summarily disappeared. “Your mother is alive,” the heron says, and beckons Mahito to enter the tower to seek answers from its master.

Part of the reason that I leave the summary so brief is that on many levels The Boy and the Heron is a deliberate fever dream of a story and to commit it to print would make me sound like I’ve stroked out. But that’s when I’m limited to text. As a film, The Boy and the Heron never feels unbelievably absurd nor inauthentic because Miyazaki sells it through visual impact. To paraphrase John Keats, beauty is truth and The Boy and his Heron is unerringly so. This is Studio Ghibli, so technical prowess in animation goes without saying; a hospital burning down should be objectively horrific but I found myself entranced by the detail, as I did for the simple flight of birds. And of course, Miyazaki’s trademark love of the Japanese countryside bleed into every frame (even when the setting goes down the proverbial rabbit hole). It is when The Boy and the Heron is most surreal, though, that its beauty does the heaviest lifting. When the warawara rise into the night sky to be reborn, all thoughts of the mechanics of such a process are washed away by the beauty of the visual and Hisaishi’s soulful score. This has always been the advantage of animation as a medium; a scene does not have to be so much realistic as it has to be compelling, and The Boy and the Heron has compulsion is spades, enough to tempt one to abandon reality altogether and just go with the flow.

But if The Boy and the Heron was all flash and no substance it would be hardly be anything noteworthy; what does it have to say? Evidently a lot, probably too much for me to dissect in short order even if I wanted to. Most obviously there’s an allegory about leaving a broken world to the next generation. It could not get more blatant than the pelicans, figuratively feeding on the future (unborn souls) to survive. They are judged and they are burnt, but they are also to be pitied. They have no power to do any different. Perhaps depressingly, tied to this are themes involving the trauma of loss, the pain of grief, the fear of inadequacy, and perhaps the need to abandon one’s childhood dreams. But can Miyazaki be without any optimism for us? Is this really the grimmest time to be alive? Ultimately, Miyazaki reminds us, the War did end.

All this is on a general level, though; I see in The Boy and the Heron a film more personal to Miyazaki. Like with The Wind Rises, I feel that he made this one for himself. Surely, the master of the tower is none other Miyazaki in metaphor. In his tower he made a world that was, despite its professed flaws, filled with imagination and wonder. In it, a kid could use their courage, find their way, make friends, and resolve their issues. The homages were in plain sight, as much Spirited Away as Princess Mononoke. And it connected generations that would otherwise share nothing culturally other than a longing for their inner child.

But Miyazaki is old. Born in 1941, at the time of writing he’s into his 80s, which is an advanced age even outside an industry like animation where both eyesight and dexterity are an asset. If you’ve been keeping up with Miyazaki’s public statements he does come across at times as a grumpy old man, full of choice words for the kids (or rather, a younger generation of adults) on his lawn. I think that on some level Miyazaki is self-aware of this and consciously tried to keep it out of his films, refraining from lecturing but instead inspiring. The foundation of the otherworld in The Boy and the Heron are literal blocks, children’s toys. Making and improving such a world requires a level of innocence nad optimism that ojii-san knows he could not indefinitely sustain. But Mahito was aware that he did not quite have it either. Indeed, who can succeed Miyazaki? More than one has been crowned the heir apparent but none can really fill those shoes. Miyazaki never even really considered his works ‘anime’; if true, they are a product unique to him. When he is gone, there will not be no more.

Perhaps The Boy and the Heron is Miyazaki convincing himself that’s okay. His passing is a natural course as well. Some children will forget, some will remember, but what they all have is the future. If anything, trying to force these things only makes it worse; the otherworld is not destroyed by malice but by a zeal to save it and a misunderstanding of its foundations. We all ultimately have to move on. I, for one, have made my peace. I hope the great auteur has too. So long, Miyazaki-sensei. May it be that, this time, you finally enjoy your retirement.

By all accounts, including a senior Ghibli executive/producer, he’s also started pre-production for his next work, whatever that may turn out to be.

Nonetheless this is a fitting finale if it does indeed turn out to be his last feature.

*already, not also

Those creatures look like the tree spirits in “Princess Mononoke”. (Ჾ_Ჾ )